WILLIAM KENTRIDGE & MILAN

Milan, Palazzo Reale 16 marzo – 3 aprile 2011

Milan, Teatro Verdi 20-21 aprile 2011

Texts from Supplemento del Sole 24 oRe – Sunday, March 13, 2011

Testi tratti dal Supplemento del Sole 24 oRe – Domenica, 13 Marzo 2011

To celebrate the International Africa Year (Anno Internazionale dell’Africa) the city of Milan has chosen to participate at several levels through the work of South African artist William Kentridge, one of his country’s most important and versatile artists. The event has been organized in association with the performance at the Teatro della Scala of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, as staged and directed by Kentridge. Milan meets with Kentridge’s many-sided creations – which range from drawing to sculpture to theatre to music to performance to video projection – and welcomes them to the city’s most prestigious venues, for a synergy that lets visitors learn more about this wonderful artist.

William Kentridge has prepared – specially for Milan – a performance that is an enactment of the relationship between visual art, theatre, music and performance. Hosted by the Palazzo Reale, the artist will present a concert together with composer Philip Miller, to be followed by a screening of the films Breathe, Dissolve, Return, whose themes are related to the lyric opera.

The Teatro Verdi will host, for the first time ever in Italy, the performance Woyzeck on the Highveld, based on the tragedy written by Georg Büchner.

This programme expresses the research of an artist who has skilfully combined the history of european culture with the difficult struggle against apartheid in South Africa.

William Kentridge is universally famous for his film saga that includes leading roles played by the business tycoon from Johannesburg Soho eckstein, and his alter ego Felix Teitlebaum. These are films that tell the story of the drama of apartheid and the guilt experienced by those who merely looked on as the restraints and violence unfolded.

Kentridge investigates the relationship with european culture, going so far as to suggest an idea of integration founded on deep ties that foster a conscience. The artist’s fascination with Büchner’s tragedy stems from the acknowledgement of a link between the drama of nineteenth-century Prussia’s violent and troubled situation, and the similar one that Kentridge witnessed in South Africa. The fragmentation crossing our times is another theme that the artist places at the centre of his images, as he seeks a way to piece it back together without, all the same, denying it; a clear example of this can be seen in Kentridge’s videos Breathe, Dissolve, Return.

An analysis of emotion and its relationship with culture and power crosses William Kentridge’s expressive panorama from one end to the other, making us participate in one of life’s greatest and most complex problems, which art has always endeavoured to analyse.

Milan presents the international audience with a series of artistic events on Kentridge as the chance to know more about the roots and the present state of cultural relations between europe and Africa: culture is an essential realm by means of which a relationship of true growth and development between two continents can once again be established.

Milan strongly believes in the path it has chosen, especially in view of the Universal expo scheduled for 2015, and presents Kentridge’s voice as evidence of this belief.

Letizia Moratti

Sindaco di Milano

Mayor of Milan

..)(..

You know, when I think of eternity, I feel so sorry for this poor old world

of ours, it’s true, I start to tremble for him… Act Woyzeck, work… keep busy,

that’s the action, understand? Eternal, eternal… you see it too, no, a thing

is eternal but then it isn’t anymore, and all it took was one second,

just a second, click, and then…

Georg Büchner, Woyzeck

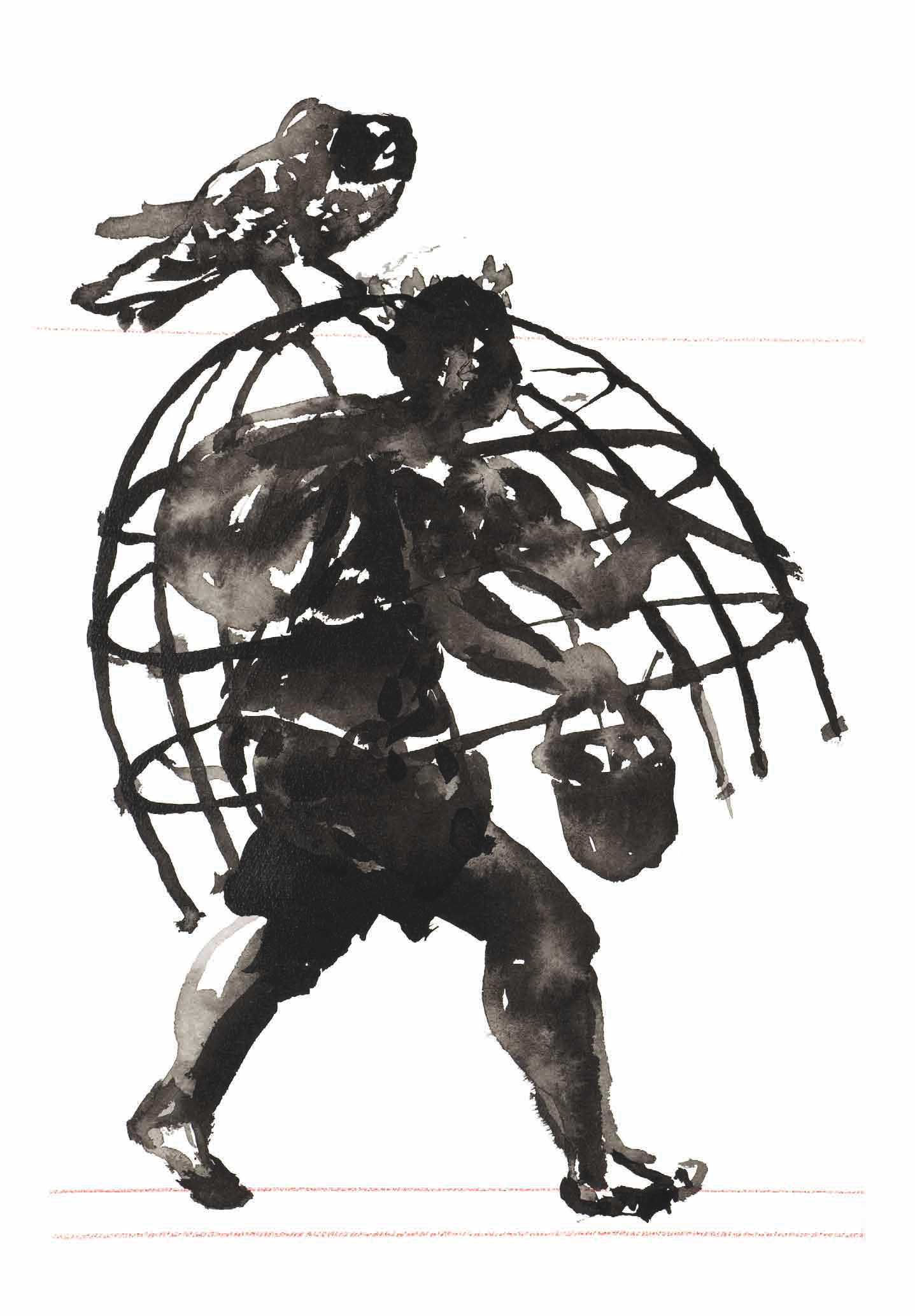

Music, cinema, theatre, animation, painting. Thanks to a brilliant commingling of genres and forms of expression what takes shape is the work and poetics of one of the key players on the international scene today. But what exactly is it all about? Pearls on the same necklace whose string is art. And the word “form” has not been chosen at random, because “forms” and figures in William Kentridge’s artistic research are one of his most distinctive stylistic ciphers.

In the animated silhouettes of his performances, films, plays, the frenzy of time, its flow, the open-ended relationship with history is turbulent.

Fragments, traces, outlines are tangible signs of human fragility, of dissolution, as well as the renewal of a fresh beginning.

Music plays a pivotal role in this process. Sounds and visions are made to dialogue in order to create the rules of a game that turns towards a unity enclosed within the apparent movement of disaggregation.

In the backdrop are life in South Africa and apartheid, the tragic experience of migration and the violent embodiment of servant-master dialectics.

The puppets in Woyzeck, along with the actors, solidly give back all the tension and contradictions of a contemporary art that Kentridge himself calls politics. It is an art that mirrors true-life facts, even the most painful pages.

And within this realm the use of technique is crucial: the importance of white and black, charcoal, pastels, the way the image is treated by subsequent changes and erasures that would seem to allude to memory’s process of reworking and sedimentation. enriched by fantasy, by imagination which endeavours to look towards the future, without forgetting the past. Breath, Return, Dissolve are the three sections that make up (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo, a video triptych shown here, allowing us to enter more directly into the world of William Kentridge. commitment, social critique, struggle, defence of civil values are just some of the features of these works. In the year Milan’s cultural council has dedicated to African nations, setting up this exhibition first of all means paying well-deserved praise to this South African artist. It also means taking the opportunity to restate the dignity and sacredness of the human being whatever his or her condition, rank, race, religion, political and social membership may be, by attempting to react, surprise, and strike through the language of the arts. In the name and for the sake of freedom and a new ethical beauty, capable of catching hold in the present – here and now – of a fragment of eternity.

Massimiliano Finazzer Flory

Assessore alla Cultura del Comune di Milano

City Councillor for Culture for the City of Milan

..)(..

Il comune di Milano partecipa alle iniziative per l’Anno Internazionale dell’Africa con un percorso a più livelli sull’artista sudafricano William Kentridge, una delle personalità artistiche più importanti e versatili del suo Paese. L’evento è proposto in concomitanza con la rappresentazione al Teatro della Scala del Flauto magico di Mozart con scene e regia di Kentridge.

Milano incontra la poliedrica creazione di Kentridge – che spazia dal disegno alla scultura al teatro alla musica alla performance alla proiezione video – accogliendola nelle sue sedi più prestigiose: una sinergia che consente ai visitatori di approfondire la conoscenza di questo grande artista.

William Kentridge ha studiato per il comune di Milano una rappresentazione che mette in scena il rapporto tra arte visiva, teatro, musica, performance. A Palazzo Reale eseguirà un concerto insieme al compositore Philip Miller, al quale seguirà la proiezione dei film Breathe, Dissolve, Return che hanno come tema il legame con l’opera lirica. Il Teatro Verdi ospiterà, per la prima volta in Italia, lo spettacolo Woyzeck sull’Highveld, tratto dalla tragedia di Georg Büchner.

Un programma che esprime la ricerca di un artista che ha saputo mettere a contatto la storia della cultura europea con la difficile lotta contro l’apartheid in Sudafrica.

William Kentridge è universalmente noto per la saga dei suoi film che hanno come protagonisti un industriale di Johannesburg,

Soho eckstein, e il suo alter ego Felix Teitlebaum. Film che raccontano il dramma dell’apartheid e il senso di colpa di chi assisteva a costrizioni e violenze. Kentridge indaga il rapporto con la cultura europea arrivando a proporre un’idea di integrazione fondata sui legami profondi che costruiscono la coscienza. Il fascino per la tragedia di Büchner proviene dal riconoscimento di un legame tra il dramma della violenza nella travagliata situazione della Prussia del XIX secolo e quello che Kentridge, in modo analogo, riscontrava in Sudafrica. La frammentazione che attraversa il nostro tempo è un altro tema che egli mette al centro delle sue immagini, cercando una via per comporla senza tuttavia negarla, come appare nei video Breathe, Dissolve, Return.

L’analisi dell’emotività e i suoi legami con la cultura e il potere attraversano tutto il panorama espressivo di William Kentridge rendendoci partecipi di uno dei grandi e complessi problemi della vita, che l’arte ha sempre indagato.

Milano propone al pubblico internazionale il complesso degli eventi artistici su Kentridge come occasione per approfondire le radici e il presente delle relazioni culturali tra europa e Africa: la cultura è una dimensione fondamentale attraverso la quale è possibile rifondare, tra i due continenti, un rapporto di autentica crescita e di sviluppo.

Milano crede in questo percorso soprattutto in vista dell’esposizione Universale 2015 e ripropone la voce di Kentridge come testimonianza di questa convinzione.

Letizia Moratti

Sindaco di Milano

Mayor of Milan

..)(..

Sai, quando penso all’eternità, questo nostro povero mondo mi fa tanta

pena, già, proprio così, mi viene da tremare per lui… Agire, Woyzeck,

lavorare… darsi da fare, ecco l’azione, capisci? Eterno, eterno… lo vedi

anche tu, no, una cosa è eterna ma poi non lo è più, ed è stato un attimo,

solo un attimo, tac, e poi…

Georg Büchner, Woyzeck

Musica, cinema, teatro, animazione, pittura. con una geniale mescolanza dei generi e delle forme espressive prende corpo l’opera e la poetica di uno dei più significativi protagonisti dell’attuale scena internazionale. Ma di cosa si tratta? Perle della stessa collana il cui filo è l’arte. e la parola “forma” non è scelta a caso, perché William Kentridge fa della ricerca sulle “forme” e sulle figure una delle sue più marcate cifre stilistiche. nelle silhouettes che si animano nei suoi spettacoli, films, performances, si agita l’inquietudine del tempo, del suo fluire, dell’irrisolto rapporto con la storia. Il frammento, la traccia, la sagoma sono segni tangibili dell’umana fragilità, della dissoluzione, così come della ricomposizione di un nuovo inizio. In questo processo la musica ricopre un ruolo fondamentale. Suoni e visioni si mettono in dialogo per comporre le regole di un gioco che torna verso un’unità racchiusa nell’apparente movimento di disgregazione.

Sullo sfondo la vita in Sud Africa e l’apartheid, la tragica esperienza della migrazione e dell’incarnazione violenta della dialettica servo-padrone.

Le marionette di Woyzeck, insieme agli attori, restituiscono nella loro solidità tutta la tensione e la contraddizione di un’arte contemporanea che lo stesso Kentridge definisce politica. Un’arte che rispecchia la realtà dei fatti, perfino nelle pagine più dolorose. e in questo ambito l’uso della tecnica è decisivo: l’importanza del bianco e nero, il carboncino, i pastelli, il trattamento dell’immagine per successive modifiche e cancellature che paiono alludere al processo della rielaborazione e sedimentazione della memoria.

Arricchita dalla fantasia, dall’immaginazione che prova a guardare al domani. Senza dimenticare il passato. Breathe, Return, Dissolve sono le tre sezioni che costituiscono (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo, un trittico in mostra, che ci permettono di entrare più direttamente nel mondo di William Kentridge. Impegno, denuncia, lotta, difesa dei valori civili sono soltanto alcune delle caratteristiche di tali lavori. nell’anno che l’Assessorato alla cultura del comune di Milano dedica ai paesi dell’Africa realizzare questa esposizione, vuol dire, anzitutto, attribuire un meritato riconoscimento all’artista sudafricano, ma significa anche cogliere un’occasione per riaffermare la dignità e la sacralità della persona umana in ogni condizione, rango, razza, religione, appartenenza politica e sociale.

Provando a reagire, sorprendere, colpire attraverso il linguaggio delle arti. in nome e per conto della libertà e di una nuova bellezza etica, capace, quest’ultima di afferrare nel contingente, qui e ora, un frammento dell’eterno.

Massimiliano Finazzer Flory

Assessore alla Cultura del Comune di Milano

City Councillor for Culture for the City of Milan

Text by Francesca Pasini

William Kentridge’s anti-entropy and the tuning up of images of the future

When Fiorano Rancati and Giordano Sangiovanni asked me to collaborate with the Teatro Verdi to bring Woyzeck on the Highveld (from Georg Büchner) to Milan, directed by William Kentridge with the Handspring Puppet company, I had recently discovered that the Teatro della Scala was planning to show Mozart’s The Magic Flute, with Kentridge’s staging and set designs. This, to my mind, was an outstanding opportunity to combine the Teatro di Figura with the installation (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo (2008), which consists of the synchronous projection of the films Breathe, Dissolve, Return, produced by Kentridge, for the “Arte contemporanea a Teatro” project sponsored by the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa – Teatro La Fenice in Venice, which I have been working on since 2004.

This idea of anti-entropy linked to the theme of the fragility of coherence is at the present time a crucial point in the lives of individuals and in the country-systems

Hence, in the year devoted to South Africa, this special tribute to Kentridge spawned across the whole of Milan: Teatro della Scala, Teatro Verdi, Palazzo Reale, Galleria Lia Rumma. We must have been protected by one of Kentridge’s stars in the firmament, because everything was coordinated spontaneously and independently.

William Kentridge is a very generous artist, and when he came to Milan to see where he could set Breathe, Return, Dissolve, he also suggested a concert with Philip Miller, a composer who has written the music for many of Kentridge’s films. It is a special concert, one in which William himself will take part, while Philip will play a piano duet with Idith Meshulam on March 15, and with Vincenzo Pasquariello during the repeat performance on March 19. But that’s not all: the live music will accompany the screening of the films Journey to the Moon, Memo, Medicine Chest, Hotel, the rhino hunting scene from Black Box/Chambre Noire, Isis Tragedie and The Plague (from the series

Carnets d’Egypte).

The exhibition at Palazzo Reale thus takes on a polyphonic dimension which fits right in with the synchronized films Breathe, Dissolve, Return, created to be projected onto the fire screen at the Teatro La Fenice during the hour just before the start of the lyric opera; at the same time it unveils a theatrical dimension. Indeed, the opening begins with the Miller and Kentridge concert, and ends with the screening of the films made for Venice (for the first time in Italy since then). In the sequence for the Teatro La Fenice, Kentridge was a prelude to the lyric opera; here, Kentridge is a prelude to Kentridge.

The Sala delle otto colonne is transformed into a sort of private theatre, as was so often the case in Italy’s ancient noble palaces, while access to the Sala delle Quattro colonne is turned into a foyer and exhibition room, where two tapestries from the preparatory work for the Shostakovich opera The Nose (Metropolitan opera, new York, 2010), the video projection of a book on a figure from (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo have been drawn, and a live concert recording can all be appreciated.

Kentridge’s linguistic keyboard (i.e. drawing, sculpture, tapestries, film, music) is evident from the start, but the common thread in the project is theatre: we find it in the films Breathe, Return, Dissolve, in the concert itself, and, obviously, in Woyzeck on the Highveld. There is also a recurring motif throughout Kentridge’s work, which is especially evident in Milan: the disintegration and need to reaggregate the fragments to understand oneself and the world.

This is how Kentridge tells the story of the birth of his films for the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa – Teatro La Fenice.

“Breathe and its companion pieces Dissolve and Return are made initially to be projected on the fire screen of the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. They are shown while the audience enters the auditorium and the orchestra is tuning up before the performance. […] one of the operas that came to mind was Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. […] I mentioned this to Philip Miller […] who was working with the idea of tuning or warming up as the basis for the sound that is part of the film. The orchestra tuning up is one of the sounds in an opera house before a performance, but there are also smallerscale events. A trombone player going over phrases of music in a corridor. A singer doing vocal warm up exercises in a dressing room. A répétiteur going over sections of the music. A whole chaotic prehistory of sound, before the clarity of the performance itself.

Philip recorded various musicians warming up. […] one of the many fragments Philip brought to the edit room was a recording of an aria from Gianni Schicchi. But when he recorded it, the singer Kimi Skota had been in cape Town and he had been in Johannesburg, so she had sung the aria to him over her cell phone. This strange recording […] became the basis for Breathe. […] I cannot remember whether I had started work on the confetti animation technique the day before I heard the music, or whether the images prompted the technique. […] But when the music and the confetti were put together in the edit suite, the rightness of the combination was clear. I had thought I would use the disintegration only in reverse, constructing images.

What the particularity of the recording showed was the backwards and forwards movement.”

(W. Kentridge, (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo, Milan, charta, 2008, pp. 19-21)

“Return. I have been working on two-dimensional sculptures. Using wire, paper, and cardboard I have made a series of tabletop figures mounted on turntables.

There is a conductor, several singers, a nose on horseback, a woman with a megaphone. […]

There is only one point from which all the elements come together in the correct relationship to each other. […] The sculptures are made to be filmed.

They need the monocular vision of a camera to function. And they will be seen as projections on the fire curtain. In this sense they are antisculptures, rejecting their three-dimensionality and hanging onto the flatness of projection. Their existence as sculptures is accidental, a result of what was needed in the film. And (or but) they are far more interesting as objects than if I had started out to make sculptures of heads or singers. […] The orchestra tunes up. […] The oboe’s ‘A.’ This picked up first by one instrument then by groups on them. The ‘A’ holds and then disintegrates again. […] The first days of the whole project were spent listening to orchestras tuning, and feeling this circular movement. The turning sculptures emerged from this impulse. The disintegration of the sculptural images was an attempt to find an equivalent to the sound that is the given of the piece – the orchestra tuning up.”

(op. cit., pp. 21-23)

“Dissolve. Many years ago I had worked with Philip Miller, Jo Ractliffe, and Jane Taylor on what was planned as a chamber opera based on the orpheus myth. […] We had tried the reflection of projections bounced off water. […] The opera project did not come to fruition. But I remembered the experiments when thinking of other disintegrations to use in (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo. […] There are points of similarity and difference to the logic of a water image, and the sound of the orchestra tuning. If the reflected image is the equivalent of silence then the ‘A’ of the oboe is the rupture of the image and the orchestra following and diverging from the ‘A’ is the image dissolving and slowly reforming itself, becoming still as the orchestra goes back to silence. But the imperatives of the orchestra are different; there is a leader who calls for silence. The nature of the arrival of silence is very different to the slow slowing down of the water. So […] there is the question of taming the natural rhythm of the water, so that it moves from the familiar movement of ripples and reflections to something where the medium is water, but the image is not simply aqueous. I know this will be a question of both speed […] of movement of what is filmed, and slowing down and speeding up the film. And of reversals, so that the disintegration of a still image can become its construction.”

And the artist concludes with the following words, which are worth stressing:

“In so far as there is a central logic behind the whole project, it is the argument of the fragility of coherence, in which the coherence and disintegration of images refers also to other fragilities and breaks. In this regard all the sections of the project are about anti-entropy, a gathering out of chaos to order, rather than a reversion from order to a state of dispersal.

With each section the work is to make the disintegration. The completed image is the simplest task. Its apparent explosion is where the concentration is – as if the opera is the easy part, the tuning up, and turning the real work.”

(op. cit., pp. 23-25)

This idea of anti-entropy linked to the theme of the fragility of coherence is at the present time a crucial point in the lives of individuals and in the country-systems. So often art knows how to intuit the changes that are about to take place, and, today, it is not really so forced to apply the “fragility of coherence” to Tunisia, egypt, Libya, hoping that we will truly find ourselves before an event of antientropy, “a gathering out of chaos to order” of the kind that will take into account the disintegration that accompanies the tuning up of images of the future.

Although it may seem mechanical, in Kentridge the connection between artistic insight and the reality in which he lives is more and more compelling, and it is a great stimulus in helping us to understand his story and our own.

In his “notes” on Woyzeck, the first opera made in 1992 with the Handspring Puppet company, from which many others then originated, we read: “It seemed to me that the anguish and desperation of Büchner’s text does not need to be locked into the context of Germany in the nineteenth century, and that the similar circumstances that exist in South Africa today make this play completely eloquent in a local setting.” Büchner’s work came to us by fragments; there was a need for order to avoid the “dispersal,” and Kentridge, even back then, had chosen to not separate from his life the history, the culture, even that from the distant past, in other words, the tragedy of South Africa just as apartheid was coming to an end.

We can safely say, then, that Kentridge encourages us to retrace our own experiences in order to dialogue with a coherence that, the more it is aware of its own inner (and outer) fragilities, the more it is transmissible.

It is moving to read Kentridge’s words in 2008 while Mediterranean Africa was heading towards a coherence, where the fragility of thousands of people became the element of the disintegration of images and repressive rules. An anti-entropy that does not seem to” revers[e] from order to a state of dispersal,” but rather to coalesce an idea of freedom.

This choice of assembling fragments is apparent, although in a different way, in the concert Sounds from the Black Box (music by Philip Miller). Various stages in the amazing anthology of Kentridge’s films, which are all connected to one another, show us a self-portrait that combines personal memories with authors that sink their roots into history: Méliès (Journey to the Moon), friends Deborah Bell and Robert Hodgins (Memo), the composer Lully (Carnets d’Egypte)… In Medicine Chest he seems to be saying that when we look at ourselves in the mirror our face holds the images of the skies, of the birds that fly across it, but also of the thoughts that we ourselves express. In this case too, fragility and disintegration are an integral part of our conscience. In Carnets d’Egypte, behind a triple Kentridge who plays the trumpet, these notes by the artist flow by: “Approaching history from the front, from the convincing substance of recent events and working backwards – from Julius ceasar for example – one can realistically go back to egypt and the pyramids, and believe in their existence; and from there, why not, even to exodus. But coming from the back, from Genesis forward, the story of Moses, the pharaoh, the exodus, is only a fable. egypt has to be both believed and disbelieved at the same time. A solo performer is not sufficient to embody this contradiction.”

Francesca Pasini

Testo di Francesca Pasini

L’anti-entropia di William Kentridge e l’accordatura delle immagini future

Quando Fiorano Rancati e Giordano Sangiovanni mi hanno chiesto di collaborare con il Teatro Verdi per portare a Milano Woyzeck on the Highveld (da Georg Büchner), realizzato da William Kentridge con Handspring Puppet company, avevo da poco saputo che il Teatro della Scala avrebbe dato Il Flauto Magico di Mozart, con regia e scene di Kentridge. Ho pensato che era un’occasione straordinaria per abbinare al Teatro di Figura l’installazione (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo (2008), che consiste nella proiezione sincronica dei film Breathe, Dissolve, Return, creati da Kentridge per il progetto “Arte contemporanea a Teatro” della Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa – Teatro La Fenice di Venezia, al quale lavoro dal 2004.

Questo concetto di antientropia collegato al tema della fragilità della coerenza è oggi un punto cruciale della vita dei singoli e dei sistemi-paese

Così nell’anno dedicato all’Africa è nata questa particolare dedica a Kentridge in tutta Milano: Teatro della Scala, Teatro Verdi, Palazzo Reale, Galleria Lia Rumma. Siamo stati protetti da una stella del firmamento di Kentridge, poiché tutto si è coordinato spontaneamente e in autonomia.

William Kentridge è un artista molto generoso, e quando è venuto a fare il sopralluogo a Milano per decidere la collocazione di Breathe, Return, Dissolve ha proposto anche un concerto con Philip Miller, il compositore e amico con il quale studia tutte le colonne sonore dei suoi spettacoli. È un concerto speciale, al quale partecipa William stesso, mentre Philip suona a quattro mani al pianoforte con Idith Meshulam il 15 marzo, e con Vincenzo Pasquariello nella replica del 19 marzo.

Ma non è finita qui: la musica dal vivo accompagna la proiezione dei film Journey to the Moon, Memo, Medicine Chest, Hotel, Rhino (da Black Box), Carnets d’Egypte (Isis Tragedie e The Plague).

La mostra a Palazzo Reale assume pertanto una dimensione polifonica che si intona ai film Breathe, Dissolve, Return, sincronizzati tra loro e nati per essere proiettati sullo schermo tagliafuoco del Teatro La Fenice nell’ora prima dell’inizio dell’opera lirica, e allo stesso tempo evidenzia la dimensione teatrale.

L’opening inizia, infatti, con il concerto di Miller e Kentridge e alla fine si accendono le proiezioni dei film per Venezia (per la prima volta in Italia dopo di allora).

Nella sequenza del Teatro La Fenice Kentridge faceva da preludio all’opera lirica; qui Kentridge fa da preludio a Kentridge.

La Sala delle otto colonne si tramuta in una specie di teatro privato, come era frequente negli antichi palazzi nobiliari italiani; mentre l’accesso dalla Sala delle Quattro colonne assume la funzione di foyer e di sala di esposizione, dove ci sono due arazzi, provenienti dal lavoro preparatorio per l’opera Il naso di Shostakovich (Metropolitan di new York, 2010), la proiezione video di un libro sul quale sono disegnate alcune figure di (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo e la registrazione dal vivo del concerto.

La tastiera linguistica di Kentridge (disegno, scultura, arazzi, film, musica) si presenta fin dall’inizio, ma il filo rosso del progetto è il teatro: lo ritroviamo nei film Breathe, Return, Dissolve, nel concerto stesso, e ovviamente in Woyzeck on the Highveld. c’è inoltre un tema ricorrente in tutta l’opera di Kentridge che a Milano trova un particolare evidenza: la disintegrazione e la necessità di riaggregare i frammenti per capire se stessi e il mondo.

Così Kentridge racconta la nascita dei film per la Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa – Teatro La Fenice.

“Breathe e le due opere collegate, Return e Dissolve, nascono inizialmente per essere proiettate sul sipario taglia fuoco della Fenice di Venezia, mentre il pubblico entra nel teatro e l’orchestra accorda gli strumenti in attesa dello spettacolo. […] Una delle opere che mi sono venute in mente è stata il Gianni Schicchi di Puccini. […] Ho menzionato la cosa a Philip Miller che stava giocando con l’idea dell’accordatura o del preriscaldamento come colonna sonora del film. L’accordatura dell’orchestra è uno dei suoni che precedono lo spettacolo in un teatro d’opera, ma ci sono anche eventi di scala minore. Un trombonista che percorre fraseggi musicali in un corridoio. Un cantante che riscalda le corde vocali nel camerino.

Un répétiteur che ripassa sezioni dello spartito. Un’intera, caotica preistoria sonora prima della squillante chiarezza dello spettacolo in sé. Philip ha registrato diversi musicisti mentre si riscaldavano. […] Uno dei molti frammenti che Philip ha portato nella sala di montaggio era un’aria del Gianni Schicchi. Quando l’ha registrata, però, la cantante Kimi Skota era a città del capo, mentre lui era a Johannesburg, per cui l’aria è stata cantata in un cellulare. Questa strana registrazione […] è diventata la base di Breathe. […]

Non ricordo se avessi iniziato a lavorare sulla tecnica di animazione a ‘confetti’ il giorno prima di ascoltare la musica o se siano state le immagini a generare la tecnica. […] Ma quando abbiamo messo insieme la musica e i confetti nella sala di montaggio, la felicità della combinazione è risultata chiara. credevo che avrei usato la disintegrazione solo al contrario, per costruire immagini, ma la particolarità della registrazione ha messo in evidenza il movimento avanti e indietro”

(W. Kentridge, (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo, trad. Ben Benraguette, Milano, charta, 2008, pp. 16-20).

“Return. Ho lavorato a sculture bidimensionali.

Usando fil di ferro, carta e cartoncino ho creato una serie di figure in piedi montate su piattaforme rotanti.

C’è un direttore, diversi cantanti, un naso in sella a un cavallo, una donna col megafono. […] c’è un solo punto da cui tutti gli elementi si incastrano l’uno con l’altro secondo il giusto rapporto. […] Le sculture sono fatte per essere filmate. necessitano della visione monocolare di una macchina da ripresa per funzionare. In questo senso si tratta di anti-sculture, poiché rigettano la propria tridimensionalità e si aggrappano alla piattezza della proiezione. La loro esistenza come sculture è accidentale, un risultato di ciò che era necessario per il film. e (o ma) sono oggetti molto più interessanti che se fossi partito col proposito di creare sculture di teste o di cantanti. […]

L’orchestra accorda gli strumenti. […] Il ‘la’ dell’oboe viene ripreso prima da uno degli strumenti, poi da intere sezioni dell’orchestra. Il ‘la’ tiene, poi si disintegra nuovamente. […] I primi giorni del progetto li spendemmo tutti ad ascoltare l’orchestra che accordava, e a saggiare questo movimento circolare. Le sculture ruotanti sono emerse da questo impulso.

La disintegrazione delle immagini scultoree era un tentativo di trovare l’equivalente del suono reso dall’opera: l’orchestra che accorda”(op. cit., pp. 20-22).

“Dissolve. Molti anni fa ho lavorato con Philip Miller, Jo Ractliffe e Jane Taylor su quella che doveva diventare un’opera da camera basata sul mito di orfeo. […] Avevamo provato la registrazione video del riflesso di proiezioni riverberate dall’acqua. […]

Il progetto non raggiunse la fruizione del pubblico, ma quegli esperimenti mi tornarono in mente mentre pensavo ad altre disintegrazioni da usare in (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo. […] ci sono punti di somiglianza e di differenza tra la logica di un’immagine acquatica e il suono di un’orchestra che accorda gli strumenti. Se l’immagine riflessa è l’equivalente del silenzio, allora il ‘la’ dell’oboe è la rottura dell’immagine, mentre l’orchestra che segue e rifugge quel ‘la’ è l’immagine che si dissolve e si riforma lentamente, tornando immobile proprio come l’orchestra torna silenziosa. Ma gli imperativi dell’orchestra sono diversi: lì c’è un direttore che richiama al silenzio. La natura di questo ritorno è molto diversa dal lento rallentare dell’acqua. e così […] abbiamo il problema di domare i ritmi naturali dell’acqua in modo che passi dal movimento familiare di increspature e riflessi a qualcosa in cui l’acqua è il mezzo, ma l’immagine non è semplicemente acquosa. So che questo dipenderà […] sia dalla velocità del movimento di quello che si filma, sia dal rallentamento/velocizzazione del film stesso.

Ma anche dalle inversioni, in modo che la disintegrazione di un’immagine immobile possa diventare la sua costruzione”. e conclude con queste parole che vale la pena evidenziare: “C’è una logica centrale dietro all’intero progetto, è il tema della fragilità della coerenza, dove la coerenza e la disintegrazione di immagini richiamano anche altre fragilità e rotture. Sotto questo aspetto, tutte le sezioni del progetto riguardano l’anti-entropia, un raccogliere e riportare il caos all’ordine piuttosto che regredire dall’ordine alla dispersione. L’opera deve effettuare la disintegrazione in ogni sua sezione. completare l’immagine è il compito più semplice. La concentrazione è tutta nella sua esplosione apparente – come se il concerto fosse la parte facile, e l’accordatura la vera opera”

(op. cit., pp. 22-24).

Questo concetto di anti-entropia collegato al tema della fragilità della coerenza è oggi un punto cruciale della vita dei singoli e dei sistemi-paese. Spesso l’arte sa intuire i cambiamenti che stanno per succedere e, in questi giorni, non è poi così forzato applicare la “fragilità della coerenza” a Tunisia, Egitto, Libia, auspicando di trovarsi realmente di fronte a un evento di anti-entropia in grado di “riportare il caos a un ordine” che tenga conto delle disintegrazioni che accompagnano l’accordatura delle immagini del futuro.

Può sembrare meccanico, ma in Kentridge è sempre molto coinvolgente l’intreccio tra intuizione artistica e la realtà in cui vive ed è un grande stimolo per capire la sua storia e la nostra.

nelle sue “note” sul Woyzeck, la prima opera realizzata nel 1992 con l’Handspring Puppet, da cui poi ne sono nate molte altre, leggiamo: “Mi è sembrato che l’angoscia e la disperazione di Büchner non fosse rinchiudibile nel contesto della Germania del XIX Secolo, ma visto che circostanze simili esistono oggi in Sud Africa, questo dramma è eloquente anche in un una situazione locale”. L’opera di Büchner ci è arrivata per frammenti, c’era bisogno di un ordine per evitare la “dispersione” e Kentridge, già allora, aveva scelto di non scindere dalla sua vita la storia, la cultura anche lontane, ovvero la tragedia del Sudafrica a cavallo della fine dell’apartheid.

Diciamo dunque che Kentridge ci stimola a ripercorrere le proprie esperienze per dialogare con una coerenza che è tanto più trasmissibile, quanto più conosce le proprie interne (ed esterne) fragilità.

Emoziona rileggere le parole di Kentridge del 2008 mentre l’Africa mediterranea sta andando incontro a una coerenza, dove la fragilità di migliaia di persone diventa l’elemento di disintegrazione di immagini e di regole coercitive. Un’anti-entropia che non sembra “regredire dall’ordine alla dispersione”, ma piuttosto riaggrega un’idea di libertà.

La scelta di ricomporre i frammenti appare, pur in modo diverso, nel concerto Sounds from the Black Box (musica di Philip Miller). Varie tappe della straordinaria antologia di film di Kentridge, collegandosi tra loro, ci indicano un autoritratto che abbina ricordi personali ad autori che affondano nella storia: Méliès (Journey to the moon); gli amici Deborah Bell e Robert Hodgins (Memo), il compositore Lully (Carnets d’Egypt)… In Medicine Chest, sembra dirci che quando ci si guarda allo specchio la nostra faccia trattiene le immagini dei cieli, degli uccelli che lo attraversano, ma anche i pensieri che noi stessi trasmettiamo.

Anche in questo caso, fragilità e disintegrazione sono parte integrante della coscienza. In Carnets d’Egypt, dietro un Kentridge triplicato che suona la tromba scorrono idealmente queste sue note: “Partendo dalla storia di oggi, dalla sostanza forte di eventi recenti, e poi retrocedendo (fino a Giulio cesare, per esempio), si può realisticamente ritornare all’egitto e alle piramidi, e credere alla loro esistenza; e da qui, perché no, si può retrocedere fino all’esodo.

Viceversa, partire dal passato, dalla Genesi in poi, e via via la storia di Mosè, il faraone, l’esodo, sarebbe fasullo. All’egitto bisogno credere e al tempo stesso non credere. Un solista non è sufficiente a incarnare questa contraddizione”.

Francesca Pasini

..)(..

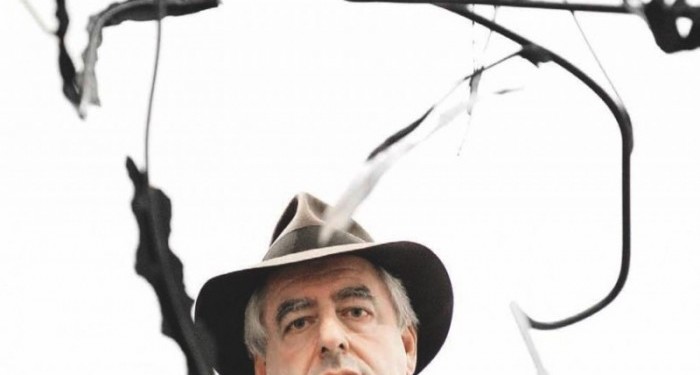

William Kentridge (Johannesburg, 1955)

Since his participation in Documenta X in Kassel in 1997, solo shows of Kentridge’s work have been hosted in many museums and galleries around the world, starting from the McA in San Diego (1998) and the MoMA in new York (1999). In 1998 an survey exhibition of his work was held at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, which was extended to other european museums in 1998-1999. A large-scale retrospective of Kentridge’s work was launched in Washington in 2001, and it then traveled on to many other cities in both the United States and South Africa. In 2004 art critic carolyn christov-Bakargiev organized another retrospective at castello di Rivoli in Turin, and this too moved on to a number of other museums in europe, canada and South Africa.

The artist’s Confessions of Zeno was commissioned by Documenta XI in 2002.

The installation Seven Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon was first shown at the Venice Biennale in 2005. In April 2005 the first production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute staged by Kentridge and directed by René Jacobs was performed at the Théâtre de La Monnaie in Brussels, after which it was shown in a number of cities, which included new York, naples and Johannesburg. In october 2005, Black Box / Chambre Noire was presented at the Deutsche Bank Guggenheim in Berlin; the performance consisted in a miniature theater with mechanical puppets, a projection and an original score by Philip Miller.

At the 2008 Sydney Biennale Kentridge presented I am not me, the horse is not mine, a solo lecture/performance; and an installation of eight short video projections of the same name. Also in 2008, Kentridge produced, as part of the “Arte contemporanea a Teatro” project, the projection (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice, and the exhibition of the same name at the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, curated by Francesca Pasini.

The year 2009 witnessed the start of a new large-scale traveling exhibition, which started out in San Franciso, and then moved on to Texas, Florida, the MoMA in new York, the Jeu de Paume in Paris, the Albertina in Vienna, followed by Jerusalem, Melbourne and Vancouver.

That same year another major exhibition opened in Kyoto, and also traveled to Tokyo and Hiroshima.

For Kentridge, 2010 began with a major retrospective at the MoMA in new York, and the premiere of his staging and design of Shostakovich’s opera The Nose at the Metropolitan opera in new York. The Nose will be performed in Aix-en-Provence in 2011 and in Lyon in 2012, after which it will return to the Metropolitan opera in 2013.

William Kentridge has received honorary doctorates from a number of universities and art institutions across the world. He received the carnegie Medal for the carnegie International, 1999-2000; the Goslar Kaisserring, 2003; the oskar Kokoschka Award, 2008; in 2010 he was awarded the Kyoto Prize for Lifetime Achievement in Arts and Philosophy.

William Kentridge (Johannesburg, 1955)

Dalla sua partecipazione a Documenta X a Kassel nel 1997, sono molte le personali di William Kentridge in musei e gallerie internazionali, a cominciare dal McA di San Diego (1998) e dal MoMA di new York (1999). nel 1998 una rassegna antologica del suo lavoro è ospitata dal Palais des Beaux-Arts di Bruxelles, per proseguire nel 1998-99 spostandosi in alcuni musei europei. Il 2001 vede il lancio dell’importante rassegna del lavoro di Kentridge a Washignton, che è poi ospitata in molte città degli Stati Uniti e del Sud Africa. nel 2004, carolyn christov-Bakargiev cura una nuova retrospettiva al castello di Rivoli, a Torino, che si trasferisce poi in alcuni musei in europa, canada e Sud Africa.

L’“oratorio” Confessions of Zeno è commissionato da Documenta XI nel 2002.

L’installazione Seven Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon è presentata alla Biennale di Venezia nel 2005. nell’aprile 2005 è realizzata la prima produzione del Flauto Magico di Mozart, al Théâtre de La Monnaie di Bruxelles, con la regia di Kentridge e la direzione di René Jacobs, uno spettacolo che gira poi in molte città, tra le quali new York, napoli e Johannesburg. nell’ottobre 2005 al Deutsche Bank Guggenheim di Berlino viene presentato Black Box / Chambre Noire, un teatro in miniatura con marionette meccaniche, proiezione e musica originale di Philip Miller.

Alla Biennale di Sydney del 2008 Kentridge presenta I am not me, the horse is not mine, un assolo composto da una lecture/performance e da otto frammenti di film.

Sempre nel 2008, realizza per il progetto “Arte contemporanea a Teatro” la proiezione (Repeat) From the Beginning / Da capo al Teatro La Fenice di Venezia e la mostra omonima alla Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, a cura di Francesca Pasini.

Nel 2009 ha inizio una nuova grande mostra itinerante, a partire da San Francisco per proseguire in Texas, in Florida, al MoMA di new York e poi al Jeu de Paume di Parigi, all’Albertina di Vienna e, ancora, a Gerusalemme, Melbourne e Vancouver. nello stesso anno un’altra mostra importante viene inaugurata a Kyoto, per poi proseguire a Tokyo e a Hiroshima.

Nel 2010 a new York hanno luogo un’ampia antologica di Kentridge al MoMA e la prima della sua messinscena del Naso di Shostakovich alla Metropolitan opera. Il Naso sarà presentato a Aix-en-Provence nel 2011 e a Lione nel 2012, per ritornare alla Mertropolitan opera nel 2013.

William Kentridge è stato nominato professore onorario presso numerose università internazionali. Ha ricevuto il premio carnegie Medal for the carnegie International per il 1999-2000; il Goslar Kaisserring nel 2003; il premio oskar Kokoschka nel 2008; il Kyoto Prize for Lifetime Achievement in Arts and Philosophy nel 2010.

Posizionare il cursore sulle immagini per leggere le didascalie; cliccare sulle immagini per ingrandirle.

Position the cursor on the images to view captions, click on images to enlarge them.

Text by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev

A Witness to momentous Changes

William Kentridge is an artist in a constant state of uncertainty. Working since the late 1970s, he is alert to the contradictions of the world at large and to those within himself, and has thus created works where fractures – in the mind, in the world, amongst humans, in artworks – remain visible. Kentridge welcomes imperfection, failures, shadows, oblique glances rather than direct views, provisional moments of beauty rather than attempts at grand accomplishments. His interests are broad, and the techniques he employs have varied widely from charcoal on paper to shadow puppetry, from torn paper figures to traditional tapestries and bronze sculptures, from live-action film to animations based on trails left by ants crawling over sugar poured on paper; from chalk on an outdoor landscape to mixedmedia installations and films projected onto objects and furniture; from set-designing, theater and opera directing to sculptural/mechanical devices; from collaborating with people from various fields to solo live performances where he interacts with his own projected image. Yet, for all this variety and openness to experimentation, he does not value innovative practice per se, nor art-historical breakthroughs in style, medium, or technique – preferring instead the realm of obsolescence. He explores how the predictive experience of perception is an activity of re-cognizing and of continuous knowledge formation; how emotions and memory interconnect with desire, ethics, and responsibility; how the shaping and shifting of subjective identities form the world. His work addresses issues of agency and inaction, public and private, subjugation and emancipation.

His continuous experiments also suggest a form of vitality, curiosity and dynamism on the one hand, but also (and at the same time) a sense of restless unease and lack of resolution on the other – a sense of constant incompleteness, as if every achievement were essentially, by its very nature of being an achievement, problematic from personal, aesthetic and political standpoints. However different and varied the languages he uses, all his works have nonetheless the immediacy of a drawing, balancing design and control with improvisation and chance.

Drawing on paper allows for no lies, since you

He felt a longing

for being where

he most needed to be

cannot over-paint like in a painting, nor can you seamlessly delete images and change elements like you can with Photoshop or digital video editing.

In his recent projects related to Šostakovic ˇ ’s opera version of Gogol’s story The Nose, Kentridge has turned to the Russian avant-garde, specifically its relations to political and social change and the collapse of its revolutionary ideals, perhaps as an indirect way to reflect on the possibility of reimagining or reactualizing hope and agency today.

He has also recently been thinking about time and modernity: looking at the development of modes of standardization of time in the industrial age of the 1800s when modern society was shaped through the interconnectedness of synchronized clocks.

He looks at how we measured time in newtonian terms, and how einstein’s early twentieth century relativity appears closer to our intuitive sense of subjective time than the “normatized” and fixed time of modern clocks. Although never explicitly pointed at by the artist, one could read his references to 19th century pneumatic clocks obliquely and metaphorically as a j’accuse of the insanity of our own age of globalization and computers, a time of digital flows of information where the need for a quasi simultaneity of intention and action is at the basis of new bio-psycho-politics. Time is a conventional structure for organizing the lives of people, and it is ever more often used today to control the most minute details of the intimate sphere of humans in global society through the Internet, a world linked through time rather than space (as colonialism was) or culture (as internationalism in the modern age was.)

Kentridge was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1955 where he still lives and works. He grew up with a sense of being remote from the centers of Western culture. When he was young, he felt a longing for engaging in the history of art made in those centers, while also a simultaneous feeling of being where he most needed to be – bearing witness to momentous historical, social and political changes in South Africa itself – as he lived through the resistance and struggle to end the racist apartheid regime which ultimately collapsed in 1994 and which always lay in the background of his work as a young artist.

Growing up in South Africa, Kentridge was acutely aware of the insidious nature of any form of authority and power in regimes based on biopolitics – the control of society through the control of our bodies rather than of our political affiliations and our economic conditions. A sense of distance from the centers of cultural power, and a feeling of simultaneous engagement in the world, provided him with both a privilege and a burden – the ability to move within complexity, to be sincere, witty, compassionate and intelligent while at the same time avoiding the ironical and cynical standpoints that characterize most intelligent and critically-conscious artmaking of our times in the West.

In the late 1980s, he began to make his well-known animated drawings or films, which he used to call “drawings for projection.” These recorded the intersection, gap and relatedness of personal and collective histories by merging narratives of love and desire, sadness and guilt with images of crowds of protestors, demonstrations and crumbling buildings and empires. These were based on filming successive moments of drawing and erasing on paper so that the time and process of making a drawing was recorded and became dilated into an extended duration. The medium and technique – drawing and erasure on paper – repeated on the formal level those same attempts at amnesia and psychic removal of the traumatic “erasures” of people in the racist regime he grew up in, so that emancipation became both a subject matter of his stories and a principle underlying the form and process of his art-making.

In Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989), Monument (1990), Mine (1991), Sobriety, Obesity and Growing Old (1991), Felix in Exile (1994) History of the Main Complaint (1996) and Stereoscope (1999) images of pathology function as metaphors of a diseased body politic. These early works chronicled the rise and fall of pin-striped magnate Soho eckstein’s empire of exploited miners and land, which finally crumbles, in parallel with the story of an alter-ego: the artistic and sensual character Felix.

Erasure gave way to shadows soon after, as Kentridge began to think more and more about the celebration of the indirect and negative forms rather than the positive and assertive ones in his works from the mid-1990s onwards, especially those stemming from Alfred Jarry’s absurd and cruel character Ubu, which became the focus of Kentridge’s works from 1996 onwards and a metaphor of a more and more outrageously violent world: jerky montages of rapid, raw, non-chronological and nonlinear sequences of processions and despots characterize these works, as in the poignant and epic projection of black anthropomorphic shapes called Shadow Procession (2000).

In 2003, he created a series of short animations inspired by late-nineteenth experimental film-maker Georges Méliès, where his own persona, filmed from the real, interacted with (and within) the drawn fictional world, as if repeating and at the same time freeing subjectivity from a sense of impotence within the sphere of the artificiality of our mediasaturated times. In 2008, these works began to also comprise elements of live performance, as if the artist had turned into a physical character in a world (our world) that had definitively and dramatically become unreal, thus needing no form of representation – the body itself had become its own shadow. conversely, these same performances also act and indicate the exact opposite, insofar as they constitute forms of resistance, celebrating embodiment and the here and now. Kentridge’s shadows were often made by tearing pieces of black paper and filming various permutations of these torn pieces that suggested figurative elements. Tearing in recent years has indeed become an ever more common practice in the artist’s work – suggesting the brutality and violence of gestures, but also, and once again, the potential that lies in apparently negative acts. We live in a world of antiviruses, applications, and quick fixes. As always, and once again, Kentridge proposes a way of seeing art and life as a continuous process of change rather than as a controlled world of certainties.

..)(..

Testo di Text by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev

Testimone di memorabili cambiamenti

W illiam Kentridge è un artista in uno stato d’incertezza permanente. Attivo fin dalla fine degli anni Settanta, registra le contraddizioni del mondo in generale e quelle del suo io interiore, e ha pertanto creato opere in cui le fratture – nella mente, nel mondo, negli uomini, nelle opere d’arte – restano visibili. Kentridge accoglie le imperfezioni, gli errori, le ombre, gli sguardi obliqui anziché diretti, i fugaci momenti di bellezza piuttosto che inseguire grandi risultati. I suoi interessi sono vasti e le tecniche che utilizza vanno dal carboncino su carta alle marionette e alle ombre, dalle figure di carta strappata agli arazzi tradizionali e alle sculture in bronzo, dal “live cinema” alle animazioni basate sulle scie lasciate dalle formiche sullo zucchero versato su un foglio; dal gesso su un paesaggio esterno alle installazioni multimediali ai film proiettati su oggetti e mobili; dalla creazione di scenografie e sculture meccaniche alle regie teatrali e operistiche; dalle collaborazioni con persone dei più svariati ambiti alle performance solistiche dove interagisce con la propria immagine proiettata. Tuttavia, nonostante questa poliedricità e apertura alla sperimentazione, Kentridge non apprezza le pratiche innovative in sé, né le evoluzioni tecniche nell’arte e preferisce invece il regno dell’obsolescenza. Analizza come l’esperienza predittiva della percezione sia un’attività di ri-conoscimento e di continua formazione di conoscenza; come le emozioni e la memoria si interconnettano con il desiderio, la morale e la responsabilità; come la formazione e la mutevolezza delle identità soggettive plasmino il mondo. La sua opera affronta temi dell’impegno e dell’inazione, del pubblico e del privato, del soggiogamento e dell’emancipazione.

I suoi continui esperimenti suggeriscono da un lato una forma di vitalità, curiosità e dinamismo, ma anche (e al tempo sesso) un senso di disagio e inquietudine e

Sentiva il desiderio di trovarsi

nel posto dove più

c’era bisogno che fosse

una mancanza di risolutezza dall’altro: una sensazione di costante incompletezza. come se ogni successo fosse sostanzialmente, per il fatto stesso di essere un successo, problematico dal punto di vista personale, estetico e politico. Per quanto siano vari e diversi i linguaggi che usa, tutta la sua opera ha l’immediatezza di un disegno dove la concezione e il controllo sono controbilanciati dall’improvvisazione e dal caso.

Disegnare su carta non permette di mentire perché non si può dipingere sopra come su una tela né si possono cancellare completamente delle immagini o cambiare degli elementi come con Photoshop o con il montaggio video in digitale.

Per il suo recente progetto collegato all’opera di Šostakovic ˇ tratta da Il naso di Gogol’, Kentridge si è ispirato all’avanguardia russa, e più specificatamente ai suoi rapporti con il cambiamento politico e sociale e al crollo degli ideali rivoluzionari, forse come un modo indiretto per riflettere sulla possibilità di re-immaginare o riattualizzare la speranza e l’impegno.

Recentemente l’artista ha riflettuto anche sul tempo e la modernità, analizzando lo sviluppo dei modi di standardizzazione del tempo nell’era industriale dell’ottocento, quando la società moderna è stata modellata attraverso l’interconnessione di orologi sincronizzati. Ha studiato come misuravamo il tempo in termini newtoniani e come all’inizio del XX secolo la relatività di einstein appaia più vicina alla nostra percezione intuitiva del tempo soggettivo che al tempo “normalizzato” e fissato dagli orologi moderni. Anche se Kentridge non l’ha mai espresso esplicitamente, i suoi riferimenti agli orologi pneumatici del XIX secolo possono essere letti obliquamente e metaforicamente come un atto d’accusa contro l’alienazione della nostra era della globalizzazione e dei computer, un’epoca di flussi digitali di informazioni dove il bisogno di una quasi-simultaneità di intenzione e azione è alla base di una nuova bio-psico-politica. Il tempo è una struttura convenzionale per organizzare la vita delle persone e oggi è sempre più usato per controllare i minuti dettagli della sfera intima delle persone della società globale attraverso Internet, un mondo collegato attraverso il tempo più che attraverso lo spazio (come era il colonialismo) o la cultura (come l’internazionalismo dell’età moderna).

Kentridge è nato nel 1955 a Johannesburg, in Sudafrica, dove ancora vive e lavora. È cresciuto con la sensazione di essere lontano dai centri della cultura occidentale. Quando era giovane, sentiva il desiderio di partecipare alla storia dell’arte di quegli stessi centri dell’occidente, ma al tempo stesso sentiva di trovarsi nel posto dove più c’era bisogno che fosse – testimone dei memorabili cambiamenti storici, sociali e politici che stavano investendo il Sudafrica – testimone della resistenza per mettere fine al regime razzista dell’apartheid, che alla fine crollò nel 1994 e che è sempre presente sullo sfondo della sua opera giovanile.

Essendo cresciuto in Sudafrica, Kentridge era profondamente consapevole della natura insidiosa di ogni forma di autorità e potere nei regimi basati sulla biopolitica: il controllo della società attraverso il controllo dei nostri corpi anziché delle affiliazioni politiche o delle condizioni economiche. Il senso di distanza dai centri del potere culturale e il desiderio simultaneo di impegnarsi nel mondo gli hanno garantito un privilegio e un fardello: la capacità di muoversi all’interno della complessità, di essere sincero, arguto, compassionevole e intelligente, evitando al tempo stesso gli approcci cinici e ironici che ai nostri giorni caratterizzano la maggior parte dell’arte intelligente e criticamente consapevole dell’occidente.

Alla fine degli anni ‘80 Kentridge ha iniziato a realizzare i suoi famosi film a disegni animati, che lui era solito chiamare “disegni per proiezione”. Questi film registrano le intersezioni, le differenze e le affinità delle storie personali e collettive, mescolando storie d’amore e desiderio, tristezza e colpa con immagini di folle di contestatori, manifestazioni e sgretolamenti di palazzi e imperi. I film sono girati registrando fotogramma per fotogramma le fasi successive del disegno e della cancellatura, dilatando così la durata del processo.

Il medium e la tecnica – disegnare e cancellare su carta – riproducono sul piano formale l’amnesia e la rimozione psichica delle traumatiche “cancellature” di uomini nel regime razzista in cui era cresciuto, e l’emancipazione diventa così sia il soggetto delle sue storie sia il principio alla base della sua arte e del suo processo creativo. In Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989), Monument (1990), Mine (1991), Sobriety, Obesity and Growing Old (1991), Felix in Exile (1994), History of the Main Complaint (1996) e Stereoscope (1999) immagini di patologia fungono da metafore di un corpo politico malato. Le prime opere registrano l’ascesa e la caduta del magnate in abito gessato Soho eckstein e del suo impero di miniere e di terre, che alla fine crolla, in parallelo con la storia di un alter ego, l’artistico e sensuale Felix.

Le cancellature cedono il posto alle ombre quando Kentridge inizia a concentrarsi più sulla celebrazione delle forme indirette e negative piuttosto che su quelle dirette e assertive nelle sue opere a partire dagli anni ‘90, in particolare in quelle ispirate all’assurdo e crudele Ubu di Alfred Jarry che dal 1996 diventa il punto focale della sua opera come metafora di un mondo sempre più oltraggiosamente violento. Queste opere sono caratterizzate dal brusco montaggio di rapide e crude sequenze non cronologiche e non lineari, di processioni di despoti, come nella intensa ed epica proiezione di forme antropomorfiche nere intitolata Shadow Procession (2002).

Nel 2003 Kentridge realizza una serie di brevi animazioni ispirate al regista sperimentale della fine dell’ottocento Georges Méliès, dove l’artista in persona, filmato dal vero, interagisce con (e dentro) il mondo disegnato, come per replicare e al tempo stesso liberare la soggettività da un senso di impotenza nella sfera dell’artificialità dei nostri tempi saturati dai media. nel 2008 queste opere cominciano a includere performance dal vivo – come se l’artista si fosse trasformato in un personaggio fisico in un mondo (il nostro) che è definitivamente e drammaticamente diventato irreale e che non ha quindi bisogno di alcuna forma di rappresentazione: il corpo stesso diventano la propria ombra.

Per contro, queste stesse performance indicano l’esatto opposto in quanto rappresentano forme di resistenza che celebrano la personificazione e il ‘qui e ora’. Le ombre di Kentridge sono spesso realizzate strappando pezzi di carta nera e filmando le loro permutazioni che evocano elementi figurativi.

Gli strappi diventano negli ultimi anni una pratica sempre più comune – suggerendo la brutalità e la violenza dei gesti ma anche, e ancora una volta, il potenziale che si trova dietro atti apparentemente negativi. Viviamo in un mondo di applicazioni antivirus e di riparazioni veloci ma, come sempre, Kentridge propone un modo di vedere l’arte e la vita in continuo processo di cambiamento anziché come un mondo di controllo e di certezze.

No Comment