L’ATELIER DI LEONARDO E IL SALVATOR MUNDI – CASTELLO SFORZESCO – SALA DEI DUCALI – MILANO

MILANO | CASTELLO SFORZESCO | SALA DEI DUCALI

LA MOSTRA

L’atelier di Leonardo e il Salvator Mundi

A cura di Pietro C. Marani e Alessia Alberti

Dal 24 gennaio al 19 aprile 2020, la Sala dei Ducali del Castello Sforzesco di Milano accoglie la mostra “L’atelier di Leonardo e il Salvator Mundi”.

Dallo scorso 16 maggio, più di 300mila visitatori hanno già preso parte alle iniziative legate al programma “Leonardo mai visto” al Castello Sforzesco di Milano, che oggi ci riserva una nuova scoperta. Il pubblico è rimasto incantato dalla straordinaria riapertura della Sala delle Asse di Leonardo da Vinci, spiegata grazie all’installazione multimediale “Sotto l’ombra del Moro”, per poi perdersi nella Milano del Rinascimento attraverso l’altro percorso multimediale intitolato “Leonardo a Milano”.

“Con l’atelier di Leonardo e il Salvator Mundi – dichiara l’assessore alla Cultura Filippo Del Corno – il palinsesto per le celebrazioni del cinquecentenario della morte di Leonardo da Vinci si arricchisce di una nuova occasione per conoscere e apprezzare la straordinarietà dell’opera del genio vinciano e della sua cerchia. Siamo orgogliosi dell’enorme lavoro di ricerca e valorizzazione del patrimonio milanese di opere leonardesche che stiamo portando avanti e della risposta di pubblico che queste celebrazioni stanno riscuotendo”.

Accanto ai percorsi multimediali, una serie di mostre dossier hanno illustrato le opere grafiche di Leonardo e della sua cerchia. Se la prima, intitolata “Intorno alla Sala delle Asse. Leonardo tra Natura, Arte e Scienza”, ha subito stupito con la scoperta di un disegno inedito attribuibile a Francesco Melzi, allievo ed erede di Leonardo, con l’ultima mostra in programma le sorprese non sono finite. Recentemente, a seguito di uno studio, un altro foglio, anch’esso custodito presso il Gabinetto dei Disegni del Castello Sforzesco e mai presentato al pubblico, è stato attribuito con certezza alla bottega di Leonardo.

L’esposizione, curata da Pietro C. Marani e Alessia Alberti, presenta al pubblico il foglio ri- scoperto, affiancandolo ad altre opere del Gabinetto dei Disegni del Castello Sforzesco e ad importanti prestiti dalla Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Il disegno oggetto della mostra, che viene qui presentato all’interno di una teca in modo da consentirne la visione di entrambi i lati e dopo un intervento di restauro condotto dall’Opificio delle Pietre Dure di Firenze, è entrato nelle collezioni civiche nel 1924 tramite un importante acquisto dal santuario milanese di Santa Maria presso San Celso.

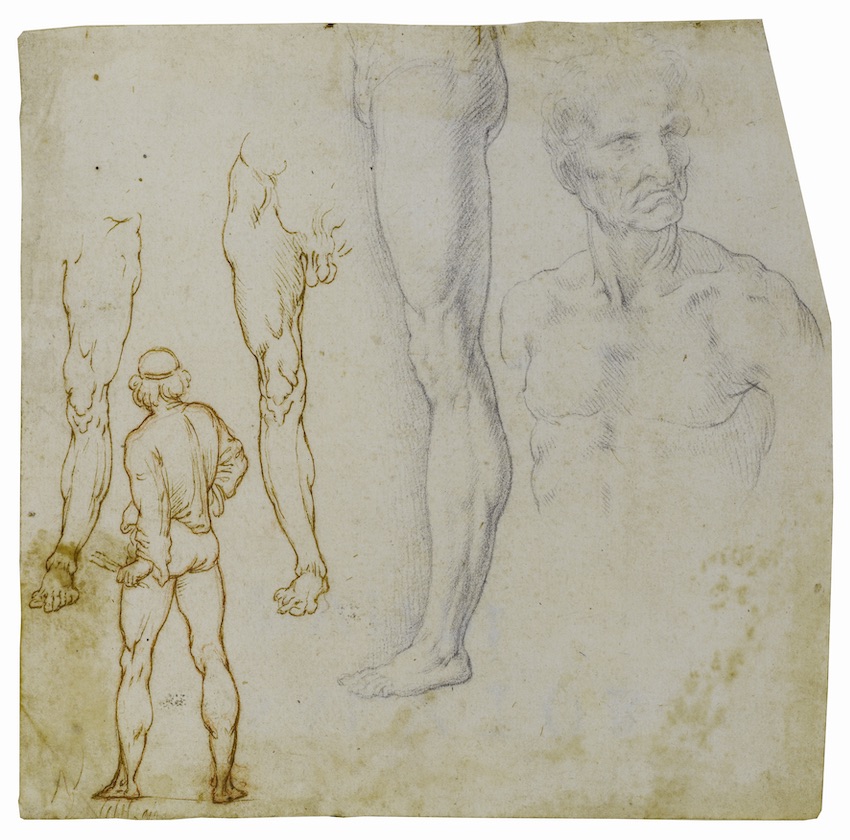

Sul recto del foglio sono disegnate figure copiate da studi anatomici di Leonardo risalenti a differenti epoche e cronologie, dal 1487 circa al 1510-13. L’attribuzione del foglio dimostra come gli originali del Maestro si trovassero ancora tutti nella bottega e potessero essere

“Una piccola ma originale e stimolante mostra che evidenzia l’elaborazione del Salvator Mundi all’interno dell’atelier di Leonardo intorno al 1510-13 e le modalità di copia dei suoi disegni anatomici da parte degli allievi. Questa esposizione aggiungerà nuovi elementi alla fortuna cinquecentesca del Salvator Mundi in ambito lombardo grazie alla presenza di alcuni fogli inediti delle collezioni del Castello Sforzesco”, afferma Pietro C. Marani.

L’esposizione, curata da Pietro C. Marani e Alessia Alberti, presenta al pubblico il foglio riscoperto, affiancandolo ad altre opere del Gabinetto dei Disegni del Castello Sforzesco e ad importanti prestiti dalla Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Il disegno oggetto della mostra, che viene qui presentato all’interno di una teca in modo da consentirne la visione di entrambi i lati e dopo un intervento di restauro condotto dall’Opificio delle Pietre Dure di Firenze, è entrato nelle collezioni civiche nel 1924 tramite un importante acquisto dal santuario milanese di Santa Maria presso San Celso.

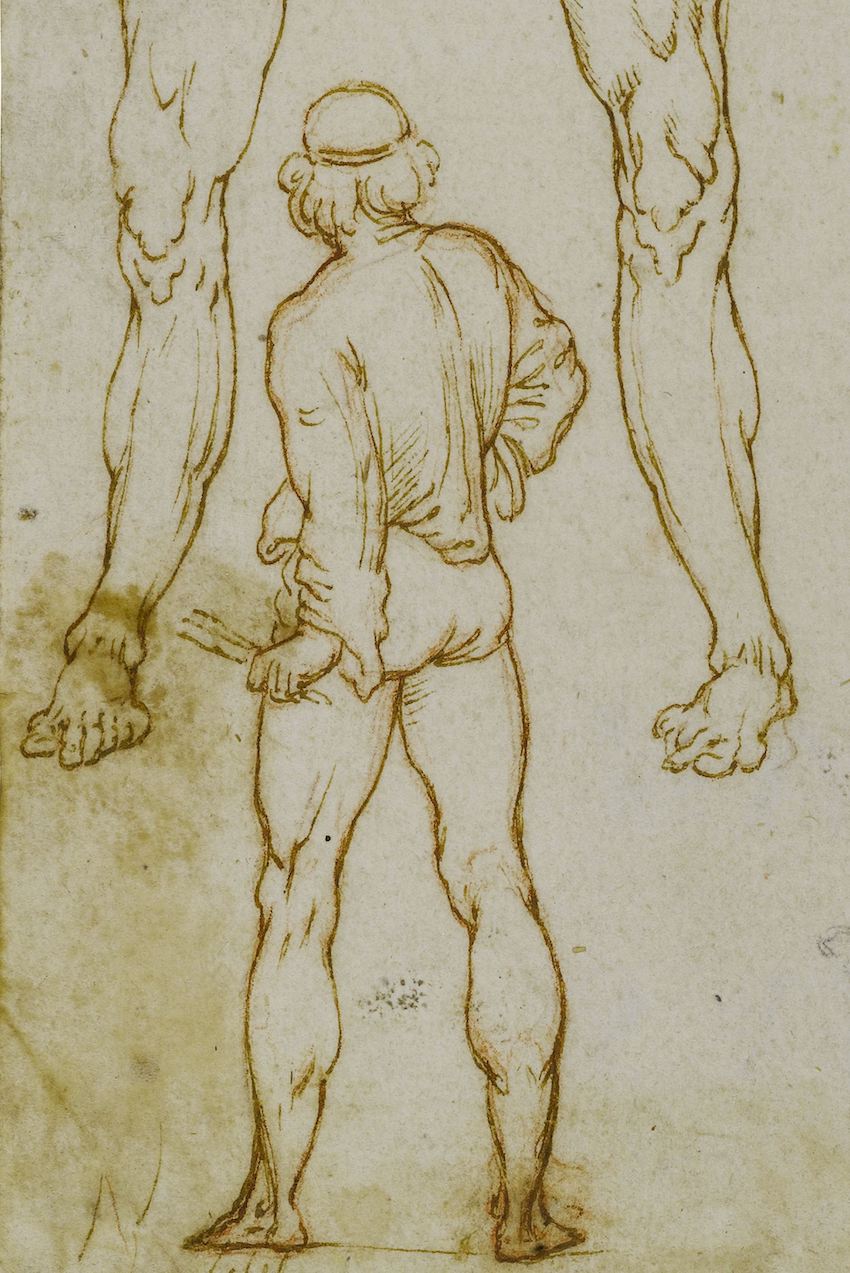

Sul recto del foglio sono disegnate figure copiate da studi anatomici di Leonardo risalenti a differenti epoche e cronologie, dal 1487 circa al 1510-13. L’attribuzione del foglio dimostra come gli originali del Maestro si trovassero ancora tutti nella bottega e potessero essere variamente copiati dagli allievi. Non solo, ma un paio di questi disegni anatomici, quelli rifiniti a penna e inchiostro, sono di buona qualità e sono stati tracciati seguendo un disegno sottostante a matita rossa, che potrebbe far pensare ad un primo labile tracciato di Leonardo.

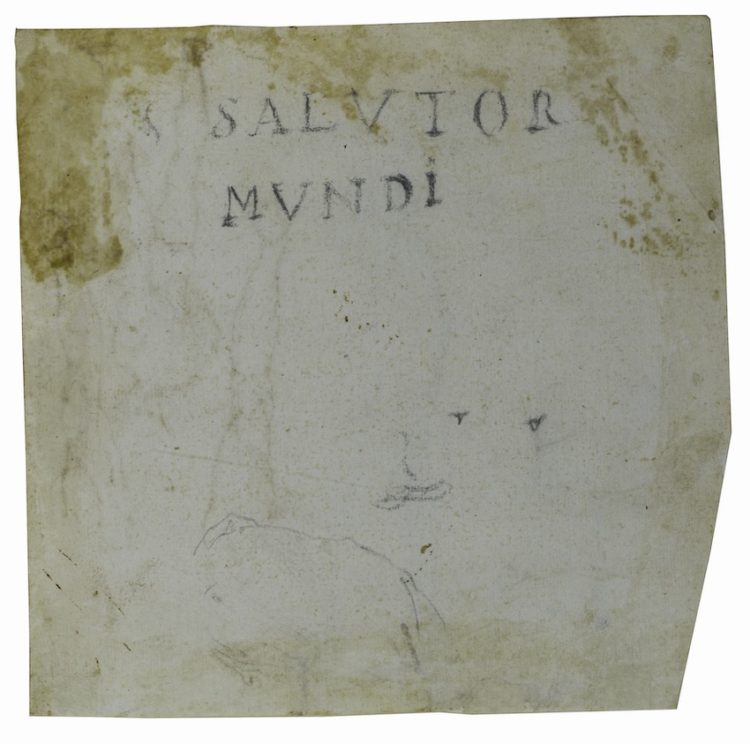

Sul verso del foglio, invece, una scritta a matita nera o carboncino rimanda a uno dei dipinti più dibattuti di Leonardo: “SALV<A>TOR MUNDI”. Forse si tratta di un primo abbozzo per un’epigrafe o una scritta esplicativa da includere eventualmente nel dipinto del “Salvator Mundi” a cui Leonardo stava lavorando proprio intorno al 1510-13 circa. È questa l’epoca a cui possono perciò risalire anche alcune delle repliche del “Salvator Mundi”, fra cui quella, parziale, firmata da Gian Giacomo Caprotti detto il Salaì, datata appunto 1511, custodita oggi dalla Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Gli studi di figure e i particolari anatomici rappresentati insieme al tipo di carta, antica ma purtroppo senza filigrana, permettono di collocare la sua realizzazione nell’ambito dell’atelier di Leonardo da Vinci e di fissarne l’epoca di esecuzione verso l’inizio del secondo decennio del Cinquecento, in un momento in cui il maestro e la sua bottega stavano evidentemente elaborando il motivo iconografico del Salvator Mundi. Ne è una prova l’iscrizione sul retro del foglio, tracciata forse nel tentativo di mettere a punto un’epigrafe o un cartiglio in caratteri romani, per l’identificazione del soggetto del dipinto.

Attorno al disegno sono esposti, con riferimento ai soggetti sviluppati sul recto, studi cinquecenteschi di anatomia, mentre per il soggetto a cui rimanda la scritta sul verso l’accostamento che si propone è con la variante del Salvator Mundi dipinta nel 1511 dall’allievo di Leonardo Gian Giacomo Caprotti detto Salaì e oggi conservata alla Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

Collocandosi accanto alla Sala delle Asse, la mostra vuole permettere al pubblico di immergersi all’interno dell’organizzazione del lavoro e del cantiere che ha realizzato anche la decorazione della grande Sala, dove sicuramente sono stati all’opera alcuni dei migliori allievi del Maestro.

“L’atelier di Leonardo e il Salvator Mundi” fa parte del palinsesto “Milano Leonardo 500”, promosso dal Comune di Milano | Cultura in occasione dei 500 anni dalla morte di Leonardo da Vinci, e rientra nel programma Leonardo mai visto, che racchiude tutte le iniziative realizzate presso il Castello Sforzesco, realizzato con il sostegno di Fondazione Cariplo, Intesa Sanpaolo, Huawei e Regione Lombardia in stretta connessione con il Comitato territoriale “Milano e l’eredità di Leonardo 1519 – 2019” e in collegamento con il Comitato Nazionale per la celebrazione dei 500 anni dalla morte di Leonardo da Vinci, ed è prodotto da Civita Mostre e Musei.

The Workshop of Leonardo and the Salvator Mundi

This small exhibition focuses on the recent discovery of a drawing preserved in the Gabinetto dei Disegni in the Castello Sforzesco, which has never been displayed before.

The sheet, which entered the civic collections in 1924 as part of a major acquisition from the Milanese sanctuary of Santa Maria presso San Celso, is presented here inside a display case, enabling it to be viewed on both sides. On the front there are copies of anatomical studies drawn by Leonardo from different periods and chronologies (1490–1510/1513 circa), on the verso are the words “SALV<A>TOR MVNDI” and a study of drapery, probably the detail of a sleeve.

The studies of figures and the anatomical details represented, together with the kind of paper, which is antique but unfortunately without a watermark, enable us to place its creation inside Leonardo da Vinci’s atelier and to establish its period of execution as towards the beginning

of the second decade of the 16th century, at a time when the master and his workshop were clearly developing the iconographic motif for the Salvator Mundi. The proof of this is the inscription on the back of the sheet, perhaps written in an attempt to perfect an epigraph or a scroll in Roman characters to identify the subject of the painting.

Exhibited around the drawing, with reference to the subjects developed on the front, are 16th century anatomical studies, while for the subject to which the writing on the verso refers the association that is proposed is with the variation of the Salvator Mundi painted in 1511 by Leonardo’s pupil Gian Giacomo Caprotti, known as Salaì, which today is preserved in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

Located next to the Sala delle Asse, the exhibition can give an idea of the organisation of the work and of the workshop that realised the decoration of the great hall, where some of the master’s best pupils undoubtedly worked.

A sheet of anatomical studies by Leonardo’s workshop

The anonymous author (or perhaps authors) of the drawing displayed in the centre of the room has the merit, first of all, of having fixed a copy of anatomical details and figures that Leonardo developed over a period of time, which he evidently made available to his pupils inside his workshop for their personal studies of at least twenty years, in a single image, as in a photograph.

The models for the two legs on the left can be related to two drawings that today are held in the British Royal collections in Windsor Castle (circa 1490); the leg in black chalk at the centre of the sheet is copied from a study preserved in London at the British Museum (circa 1506-1510), while the figure seen from the rear bran- dishing something in his left hand comes, albeit as a mirror image, from two drawings in the Biblioteca Reale in Turin, both relating to the Battle of Cascina (circa 1505-1508). Finally, in the male bust on the right we see the reflection of some late studies on the anatomy of an old man, held at Windsor Castle, from 1510-1511.

The technique of execution in the left part of the drawing is interesting, as it has an initial drafting in red chalk, the outline of which was gone over later in pen. This tracing is very recognisable in the figure viewed from behind, but it is also present in the leg to the right of this, a detail that is characterised by left-handed shading, a particular feature of Leonardo’s own graphic work. An intervention by the master’s own hand could perhaps be read as being in this first drafting in red chalk, later reinforced by a pupil, as can be seen in various drawings of his.

Exhibited alongside the sheet at the centre of the exhibition are some drawings – one contemporary, the others from the late 16th century – that attest to the success in Lombardy of the subjects portrayed by Leonardo and the method applied by the master in representing the human figure, as shown in many of his letters, many of which, after the master’s death in Amboise, were taken to Milan by his pupil and heir Francesco Melzi.

The Salvator Mundi in Leonardo’s workshop

On the verso of the sheet exhibited at the centre of the room there are some elements that can be associated with the development of the iconographic motif of the Salvator Mundi within Leonardo’s workshop: in addition to the writing, we can clearly recognise the sketch of drapery, perhaps the study for a sleeve. The chronology of Leonardo’s drawings copied onto the front of the sheet (datable between 1490 and 1510/1511 circa) provides the tools to also establish the chronology of our drawing, suggesting a dating of soon after 1510.

The iconography of the Salvator Mundi corre- sponds to the type of Christ represented half- length with his right hand giving a blessing and with a glass sphere in his left hand. Of Byzantine origin, this motif also met with a certain success in Europe from the 15th century onwards and there are various examples of it between the late 15th and early 16th centuries. One possible precedent for the Leonardesque interpretation of the subject has been identified in a small canvas by Melozzo da Forlì (today in Urbino in the National Gallery of Le Marche), which the master from Vinci might have gotten to know on the occasion of his trip to Urbino in 1502.

There is evidence for Leonardo’s project idea for a Salvator Mundi in two of his red chalk drawings with details of drapery, now in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, and in some paint- ed versions, the best known among which, on which Leonardo himself supposedly worked directly, is the one acquired for a record sum in 2017 by an Arabian prince. It would appear to correspond to the model from which, in 1650, the engraver Wenceslaus Hollar took the subject for one of his well-known etchings (a reproduction of which is exhibited in the last display case, work no. 10).

The variant that is presented here – with Christ’s head alone, without the particular hand gesture and the glass sphere – is a work by Leonardo’s pupil Gian Giacomo Caprotti, known as Salaì: the painting bears his signature and is dated 1511; it reflects the existence of a Leonardes- que prototype that at the time was perhaps not yet finished.

Two Milanese sheets from between the late 16th century and the early 17th, coming from the group of Santa Maria presso San Celso, one of which already attributed to Simone Peterzano (work no. 8), attest to the persistence of interest in this iconography.

The drawing books from the Milanese sanctuary of Santa Maria presso San Celso and the so-called ‘Fondo Peterzano’

The majority of the sheets from the Gabinetto dei Disegni in the Castello Sforzesco that are on display here, including the work at the centre of the exhibition, originate from a group of over two thousand six hundred drawings that the Municipality of Milan acquired in 1924 from the vestry of the Milanese sanctuary of Santa Maria dei Miracoli presso San Celso.

This important section, which includes works by various schools – particularly the Milanese and Lombard schools between the 16th and 17th centuries – is known above all for being associated with an artist trained in Venice called Simone Peterzano, who was Caravaggio’s teacher in Milan.

Between the 1930s and 1950s a significant set of works attributable to him and his workshop, together with other sheets of heterogeneous origin, was selected to constitute the so-called ‘Fondo Peterzano’, which can be defined as an attempt at a critical organisation of the collection, with a view to bringing together the over one thousand works referable to Peterzano and his pupils that were to be found inside the Gabinetto dei Disegni in the Castello Sforzesco.

By virtue of the origin of the San Celso group in the sphere of artists’ workshops and in any event of their artistic training (perhaps also in the local Accademia di San Luca), there are many studies of anatomical details present in it (such as the drawings that are exhibited here in the first part of the itinerary).

At the time of their entry into the civic collections, the drawings were glued onto the pages of two large tomes and they were probably conserved in this way from the 17th century onwards. The works on display here still bear the traces of this mounting technique and their subsequent separation from the pages of the volumes, as can be seen in the glue residues and some minor tears. In recent months another rare specimen associated with Leonardo’s atelier has emerged from this ancient graphic fund of incredible abundance and quality and this has been presented to the public in this same room, namely a small red chalk study depicting a tuft of anemones (reproduced on this panel). The precious detail, which seems to have been portrayed from life, probably a work by Francesco Melzi, was taken up by a pupil of Leonardo and translated into a painting on a panel with the story of Leda (Florence, Uffizi), recognised as one of the variations of a lost original by the master of Vinci.

No Comment