THE CLOWN OF THE CLOWNS, DAVID LARIBLE, TEATRO VITTORIA | ROME

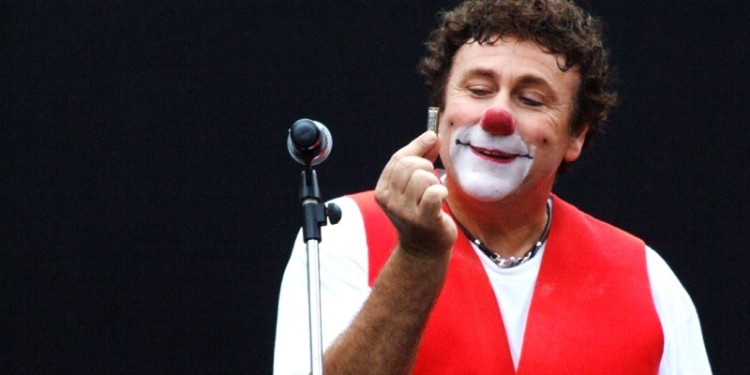

The Clown of the clowns, David Larible

National Opening – Teatro Vittoria – Rome

08 – 27 February 2011

Text by Roberta d’Errico

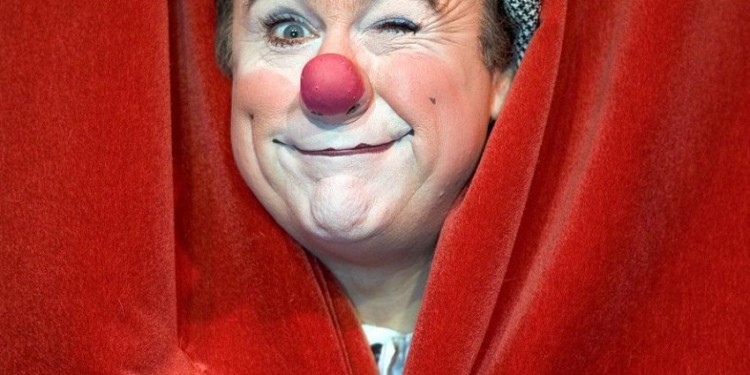

The curtain rings up on the stage full of the whole paraphernalia attaining to the circensian tradition: mirror on the small table, make up for face, masks, gleaming clothing, a piano and many other musical instruments. The soft lighting makes oneiric the ambience of the scene flooded with smoke. The time is halted like an enchantment, in a trip through the centuries. The white clown Gensi is there, played by Estephan Kunz: His face was made-up coherently to the name of his figure, he has the poise and the austere bearing that the tradition seeks.

To the piano a musician starts to play the music, the white clown backs the pianist using a long saw. Who could have ever thought that it can ring harmonious sounds when bent in a particular manner. Still the clowns are able to set the objects up to life, to make them spring unthinkable things for us.

A new character arrives on the stage: here it is, David Larible, in the cleaner’s shoes a little bit unprepared and clumsy, his presence is bothering the musical performance of the white clown. A contested relation is coming out in the light between the white clown and the one that will become the stately clown in a short time. The cleaner wishes to share that magical world because is spellbound for the objects put on the stage. He tries to play an instrument any time he is alone on stage far from the white clown’s stern look, but as soon as Gensi reappears he deprives of it. At the end with no instruments to be played our character makes music by a small accordion which has been hidden in his mouth, but the white clown’s attempts to prevent him from playing it, causes his swallow of the instrument. So we witness the first clear quotation of Chaplin’s world with Larible hiccupping at the music of the accordion, just like Chaplin was hiccupping at the music of the whistle in Luci della Città (City Lights, 1931).

Again alone on the stage, Larible initiates some conjuring tricks executed through invisible objects with the cooperation of a person from the audience and supported by his extraordinary mime. Our cleaner decided to be a real august clown, but this is possible only if he demonstrates to Gensi he has histrionic attitudes and ability to be a standing joke. So we attend to an initiation rite and notwithstanding the white clown’s hesitations, the ceremony of taking the true and real habit of a stately clown can have a start. And then Larible takes a sit at the make-up small table and at the music of Vesti la Giubba , played by Gensi, very famous aria from Mascagni’s opera Pagliacci, he transforms himself under our eyes: red nose, made-up face, hat, large and strange clothes, great shoes. The scenery got a double implication: it seems that the gift to make somebody laugh is a inward necessity and on the contrary who is not able to express himself get overcome by sadness.

The first half of the performance comes to a stop and the second one begins with the predominant audience interaction. The mastery of the stage and the knowledge of all the aspects of the performance appear in such a phase when Larible has no problems to involve even the children who feel at their own ease with gag that have the simplicity of the complicated things.

Now Larible offers a poetic solo. The curtain is lowered and he is on the stage-box. The lighting is dimmed and an ox eye is on. Larible begins a funny fight with the light, he tries to put it away from him but it comes back. Now Larible plays with it like in a play with a ball. It is possible to recognize in his movements the exact reproduction of those performed by Chaplin’s motion picture Il Grande Dittatore (The Great Dictator, 1940) when he plays with the map of the world. The turn comes to an end when Larible captures the light and makes it fall in a bucket.

The performance goes on with involving the adult and the younger audience, grouped on the stage. Larible shows his capabilities to manage unexpected and unforeseen events with people unaccustomed to be on stage not knowing of being able to play roles and interpretations.

Larible is able to make sure that each of the chosen person, will take a little bell (in spite of the white clown’s warnings not to touch them) and sound it, at his signal, backing the piano music. The performance grows rich with a great involvement of the audience when Larible entrusts the improvised helpers with different unusual and strange instruments, becoming in so doing the conductor of the grotesque characters forming the particular orchestra. The meaning of the performance seems to be just this one: we can see it by our eyes the passage from normal to exceptional situations.

And again Larible involves three young fellows of the audience, giving them some recommendations, that he is successful in doing them mime by mouth the singing and by gestures the passions and the feelings of some aria of opera acting a sort of puppet living theatre in which he is the master who moves the people invisible threads.

The performance is coming to the end. The stately clown finished his time, must go back to being a cleaner. There is sadness in the atmosphere. The white clown is on stage and watch the stately clown undressing. The movements that Larible does, in taking off his own make-up, in looking at himself in the mirror with melancholy, calls back to the memory the scene of Luci della Ribalta (Limelight, 1952) in which Chaplin/Calvero looks himself in the mirror and takes off his own make-up with a look of despair. In this latest case the despair of our stately clown originates from the lost ability to raise a laugh as far as the world doesn’t feel like to raise a laugh any more.

But then the white clown begins playing and singing the Charlie Chaplin’s song with which the motion picture Tempi Moderni (Modern Times, 1936) got to an end. The stately clown is by the time in his usual clothing, he is sad and depressed, but it is just the white clown that neglecting his traditional severity guise, get near him and make him understood that he must not loose all hope, but smile. And thus, smiling and arm in arm, just like the final scene in the motion picture, Gensi and Larible leave the stage together with their backs to the audience, because the smile goes beyond the performance, because if we smile in our life we will love to smile even on the stage.

When the curtain is lowered, Larible comes back on the stage having no scene dress on, now, just to greet the Rome audience, capital city of his native land and with Gensi sing the Nicola Piovani’s song Quanto t’ho amato. A debt of love to our Country and for a world full of magic, of music and of feelings in which the words have no matter.

Roberta d’Errico

Theatre Editor

Translated by Salvatore Rollo – at salvatore_rollo@fastwebnet.it

Davide Larible, Il clown dei clown

Prima nazionale al Teatro Vittoria

Roma dall’8 al 27 febbraio 2011

Il sipario si apre sulla scena che contiene l’intero fraseggio della tradizione circense: lo specchio sul tavolino, i trucchi per il viso, le maschere, gli abiti scintillanti, un pianoforte e tanti altri strumenti musicali. Le luci soffuse rendono sognante l’atmosfera della scena inondata di fumo. Il tempo è sospeso come in un incantesimo, in un viaggio nei secoli. C’è il clown bianco Gensi, interpretato da Estephan Kunz: ha il volto truccato in coerenza con il nome della sua figura, ha il portamento elegante e austero che la tradizione richiede.

Un musicista, seduto al piano, dà inizio alla musica, il clown bianco accompagna il pianista usando una lunga sega. Chi potrebbe mai pensare che quest’ultima, piegata in un particolare modo, possa produrre suoni tanto armonici. Ma i clown hanno il potere di dare anima agli oggetti, di far scaturire da essi cose impensabili per noi.

In scena arriva un nuovo personaggio: è lui, David Larible, nei panni di un uomo delle pulizie un po’ sprovveduto e impacciato, che con la sua presenza disturba l’esecuzione musicale del clown bianco.

Comincia a delinearsi il rapporto contrastato tra il clown bianco e quello che tra breve diverrà il clown augusto. L’uomo delle pulizie, incantato dagli oggetti posti in scena, desidera prendere parte a quel magico mondo. Ogni qual volta questi rimane solo sulla scena lontano dallo sguardo severo del clown bianco, tenta di suonare uno strumento, ma non appena Gensi ricompare glielo sottrae. Alla fine, non trovando più nulla da suonare, il nostro personaggio utilizza una minuscola fisarmonica che nasconde in bocca, ma i tentativi del clown bianco di impedirglielo fanno si che la inghiotta. Assistiamo così alla prima esplicita citazione all’universo chapliniano con Larible che singhiozza a suon di fisarmonica, come Chaplin singhiozzava a suon di fischietto in Luci della città.

Di nuovo solo sulla scena, Larible dà inizio a giochi di prestigio eseguiti con oggetti invisibili e sostenuti dalla sua mimica eccezionale e con la collaborazione di una persona del pubblico. Il nostro uomo delle pulizie ha deciso che vuole essere un vero clown augusto, ma perché ciò sia possibile deve dimostrare a Gensi di possedere doti istrioniche e capacità di far ridere. Assistiamo dunque ad un rito di iniziazione e, nonostante le perplessità del clown bianco, la vestizione di Larible in vero e proprio clown augusto può avere inizio. E così, Larible si siede al tavolino da trucco e, sulle note di Vesti la giubba celeberrima aria dell’opera Pagliacci eseguita da Gensi, si trasforma sotto i nostri occhi: naso rosso, volto truccato, cappello, abiti larghi e stravaganti, scarpe grosse. L’atmosfera ha un doppio risvolto: sembra dirci che far ridere è una necessità interiore per chi ha questo dono, ma che se non può esprimersi si tramuta in tristezza.

Termina così la prima fase dello spettacolo e ha inizio quella in cui l’interazione con il pubblico diviene preponderante. La padronanza del palcoscenico e la conoscenza di tutti gli aspetti dello spettacolo emergono in questa fase in cui Larible non ha problemi a coinvolgere anche bambini riuscendo a metterli a proprio agio e a coinvolgerli in gag che hanno la semplicità delle cose complesse.

Arriva il momento in cui Larible ci offre un assolo poetico. Il sipario si chiude e lui è sul proscenio. Le luci si abbassano e appare un occhio di bue. Larible inizia una divertente lotta con la luce, cerca di allontanarla da sé spingendola via, ma lei ritorna. Ora Larible gioca con lei, come con una palla, impossibile non ravvisare nei movimenti una esatta riproduzione di quelli eseguiti da Chaplin nel momento in cui, ne Il dittatore, gioca con il mappamondo. Il numero si chiude con Larible che cattura la luce facendola cadere in un secchio.

Lo spettacolo prosegue con il coinvolgimento di pubblico adulto e più giovane, in gruppo sul palcoscenico. In queste circostanze, Larible dimostra di avere una profonda capacità di gestire l’imprevisto e l’improvviso, portando le persone, non abituate alla scena, a eseguire interpretazioni che queste non sapevano di poter realizzare.

Larible riesce a far si che ciascuno dei prescelti prenda una campanella (nonostante le raccomandazioni del clown bianco di non toccarle) e la suoni, al suo cenno, seguendo la musica del pianoforte. La performance si arricchisce quando Larible affida agli improvvisati collaboratori strumenti diversi, insoliti e stravaganti, divenendo il direttore della particolare orchestra di elementi grotteschi, con grande partecipazione del pubblico. Il senso dello spettacolo sembra essere proprio questo: il passaggio, visibile sotto ai nostri occhi, da situazioni normali a situazioni eccezionali.

E ancora Larible coinvolge tre giovani del pubblico e impartendo loro alcune raccomandazioni riesce a far mimare loro, con la bocca, il canto e con i gesti le passioni e i sentimenti di alcune arie di lirica animando una sorta di teatrino di marionette viventi in cui lui è il marionettista che muove i fili invisibili delle persone.

Lo spettacolo sta finendo. Il clown augusto ha terminato il suo tempo, deve tornare ad essere un uomo delle pulizie. C’è tristezza nell’aria. Il clown bianco è in scena e assiste alla svestizione del clown augusto.

Nei movimenti che Larible compie, nello struccarsi, nel guardarsi allo specchio con malinconia, la nostra memoria vola alla scena di Luci della ribalta, in cui Chaplin/Calvero si guarda allo specchio e si strucca il volto con uno sguardo di disperazione. Disperazione nata in quest’ultimo caso per la perduta capacità di far ridere, per il nostro clown augusto perché sembra che il mondo non voglia ridere più.

Ma ecco che il clown bianco inizia a suonare e a cantare la canzone di Charles Chaplin con cui termina il suo film Tempi moderni. Il clown augusto ha ormai ripreso i suoi abiti consueti, è triste e sconsolato, ma, è proprio il clown bianco che, abbandonata la tradizionale veste di severità, si avvicina a lui facendogli capire che non tutto è perduto, basta sorridere. E così, con il sorriso e sottobraccio, proprio come nel finale del film, Gensi e Larible lasciano insieme il palcoscenico, dando le spalle al pubblico, perché il sorriso va oltre lo spettacolo, perché se si sorride nella vita ci sarà desiderio di sorridere anche a teatro.

Quando il sipario si chiude Larible, ormai senza abiti di scena, torna sul palcoscenico per salutare il pubblico di Roma, capitale del suo paese di origine e insieme a Gensi canta la canzone Quanto t’ho amato di Nicola Piovani. Un tributo d’amore per il nostro paese e per un mondo pieno di magia, di musica e di sentimenti in cui le parole non contano.

Roberta d’Errico

No Comment